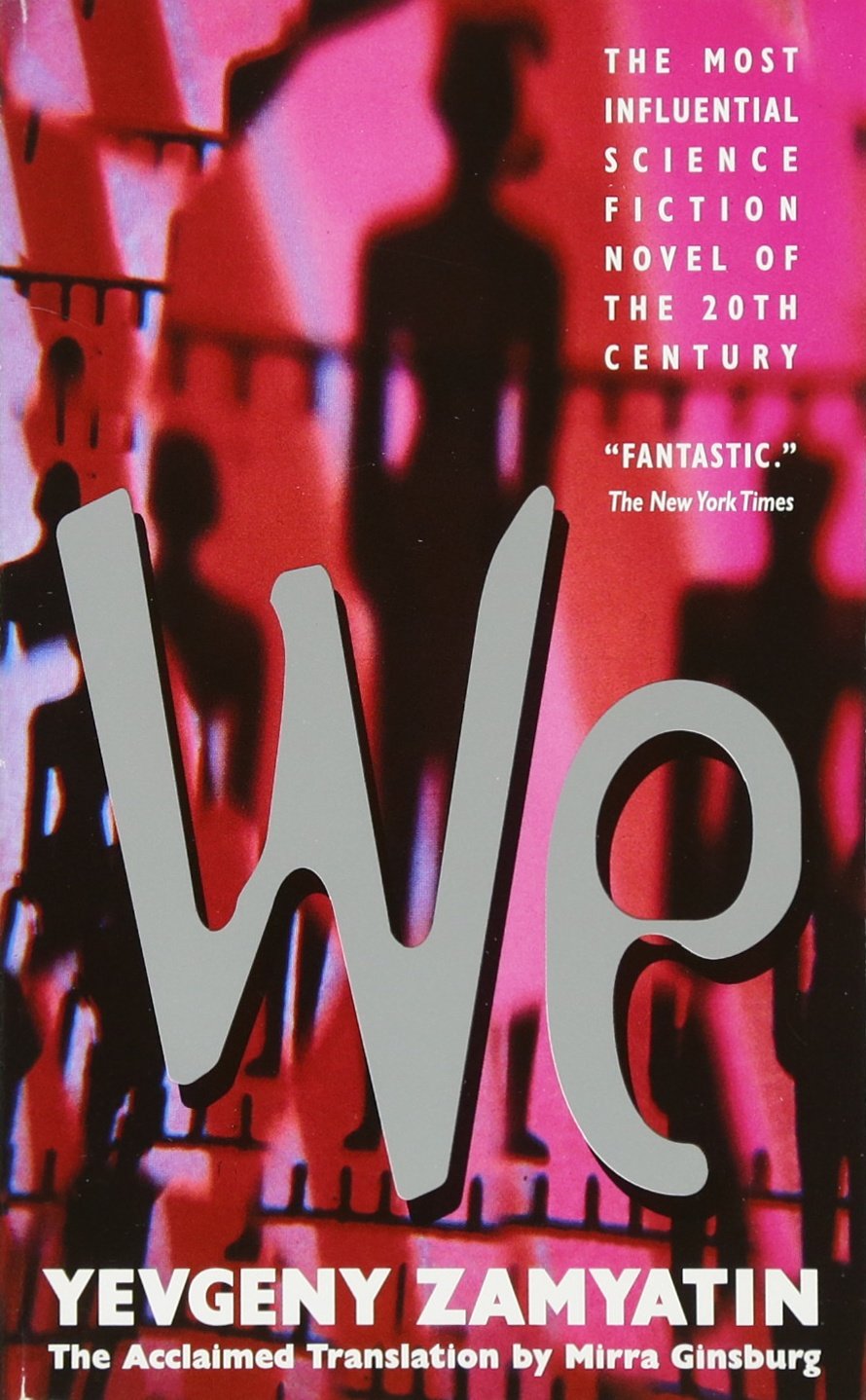

We

Before Orwell’s Big Brother and Huxley’s soma, there was Zamyatin’s One State—a glass-walled society where citizens are numbered “ciphers,” emotions are mathematical equations, and rebellion begins with a single illicit tear. Written in 1920 and banned in the Soviet Union until 1988, We isn’t just the prototype for all dystopian fiction; it’s a chillingly precise diagnosis of how technology enables totalitarianism. The narrator D-503’s gradual awakening to irrational human desires—love, privacy, chaos—mirrors our own era’s tension between digital convenience and human autonomy.

Zamyatin’s genius lies in framing surveillance as voluntary. Citizens proudly report neighbors’ infractions because they believe transparency equals purity. The Green Wall separating the ordered State from the chaotic natural world echoes modern digital boundaries: walled gardens, algorithmic curation, and the illusion that “if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.” When D-503 undergoes the “Great Operation” to remove his imagination (a surgical lobotomy), it becomes a terrifying metaphor for how we willingly surrender cognitive sovereignty for perceived security—accepting opaque algorithms that shape our thoughts, desires, and political realities.

This isn’t merely historical curiosity. We directly inspired Orwell (who reviewed it in 1946) and Huxley, but its relevance has sharpened in the age of facial recognition, social credit systems, and predictive policing. Where 1984 fears punishment and Brave New World fears pleasure, We fears perfection—the seductive lie that human complexity can be optimized away. For security professionals, it’s a foundational text: the first literary warning that technology without ethical constraints doesn’t just enable oppression—it redefines what it means to be human. Read it not as prophecy, but as a mirror held to our own glass-walled digital lives.